Prejudice is a chain, it can hold you. If you prejudice, you can’t move, you keep prejudice for years. Never get nowhere with that. (Bob Marley)

In the wake of the first presidential debate, a lot of commentary has predictably gone down about the big moments. Trump responding “That’s business” to Hillary’s description of the devastating losses suffered by poor and middle-class Americans in the wake of the 2008 financial meltdown. Trump crowing “That makes me smart” to Hillary’s assertion that he paid no income taxes for some number of years. These were moments that deserved media attention. They reveal character, attitude, values or lack of. But for me, the most amazing point in the debate occurred here:

Lester Holt: Do you believe that police are implicitly biased against black people?

Hillary Clinton: Lester, I think implicit bias is a problem for everyone, not just police. I think, unfortunately, too many of us in our great country jump to conclusions about each other. And therefore, I think we need all of us to be asking hard questions about, you know, why am I feeling this way? [my italics]

What makes this a standout is its rarity and authenticity. We expect political debates to paint policy with a broad brush: I’m for this. I’m against that. But here is Hillary suddenly departing from that script and speaking as a human being about the (our) human condition. With these words, she set every American a true challenge.

Assumptions

Assumptions—we all make them. We see someone on the street, in the gym, at the supermarket. Without any attempt to engage the person, we take a slapdash mental survey and rush to judgment. In nanoseconds, we register race, ethnicity, gender/transgender, age, any obvious physical or cognitive disabilities.

Requiring closer scrutiny, but equally in the assessment mix, is class. Class gets tricky because it runs along two separate axes that may or may not intersect: education and income. But our eye is not fooled for long. An educated person would never speak in that manner, hang out at that bar, make that mistake. A person of means would never drive that car, live in that neighborhood, frequent that diner. Nothing is off the table: weight, clothing, hair style, accent. We note them all.

Requiring closer scrutiny, but equally in the assessment mix, is class. Class gets tricky because it runs along two separate axes that may or may not intersect: education and income. But our eye is not fooled for long. An educated person would never speak in that manner, hang out at that bar, make that mistake. A person of means would never drive that car, live in that neighborhood, frequent that diner. Nothing is off the table: weight, clothing, hair style, accent. We note them all.

As I mentioned in my last post, sizing up people and situations is developmental and has its evolutionary purpose: to distinguish a threatening situation from a non-threatening one. Every seven-year-old does it. It’s the rush to judgment in non-threatening situations that’s the problem. And no, someone being of a race or sexual orientation or class different to our own does not constitute a threat.

Not My Kind

My parents lived for some years in a gated community. The houses, with minor variations in floor plan, were indistinguishable. The community covenant permitted owners to “individualize” their home by choosing one of three colors for their front door. The options? White, off-white, and ivory. (God forbid you should have one beer too many. You’d never find your own house.) There were other rules—many—including no clotheslines, no leaving your garage door open (!), and no pick-up trucks.

So, did all this homogeneity produce a sense of well-being and harmony? Did these cloistered homeowners feel secure in the knowledge they need never encounter people different from themselves in their immediate environment? No, instead they looked for ever smaller differences, magnifying them until they assumed enough significance to point a finger: Not our kind.

It would be easy to feel superior to this example. Most of us don’t live in gated communities, and many of us wouldn’t wish to. But we do live in divisive times. The Us vs. Them mentality permeates every aspect of our polarized culture.

Us vs. Them

Trump calls a Latina “Miss Housekeeping,” and we all recognize this as a racial/ethnic/gender slur. In this instance, Us vs. Them is those who are biased against Latinos and/or women, and those who aren’t. But there’s a second part to this: Why do we all understand this is a slur—what implicit bias do we hold that equates a “housekeeper” with someone of lesser worth?

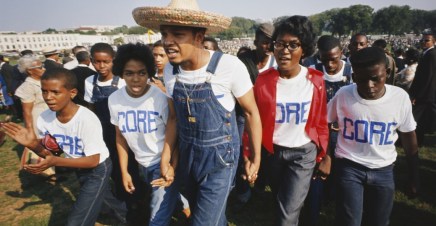

Us vs. Them is frequently a triumph of fear over fact. Since 9/11, a growing number of non-Muslim Americans have trouble seeing a Muslim American without thinking “potential terrorist.” In their fear, people buy into propaganda that Muslims are overrunning the country. Fact: Muslim Americans represent only 1% of the total U.S. population. Fact: Muslim Americans have been crucial to helping law enforcement unearth terror suspects. Fact: Hate crimes against Muslim Americans are at their highest levels since 9/11.

Stereotyping is not the sole property of any particular party affiliation, socio-economic, religious, or cultural group.

Stereotyping is not the sole property of any particular party affiliation, socio-economic, religious, or cultural group.

Mindful of the history/origins of the Ku Klux Klan, angered and upset by the 2015 racist murders of nine black members of Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church, how many of us hear a white person with a southern accent, and bristle: Racist, Confederate flag-flying, cracker thug!

And that was exactly Hillary’s point: No one is immune. At some level, whether deep-rooted and multi-generational or free-floating and vague, we all have a personal acquaintance with implicit bias.

Breaking The Silence

I had an encounter in the supermarket this summer that opened my own eyes. I was standing in a long line at checkout. Directly behind me were two men. One middle-aged, one older. Both white. Both dressed in short-sleeve plaid shirts. Work pants. They looked like Joe-the-Plumber’s (political/media stereotype) cousins. High school education. Maybe a year of community college. All this went through my brain in three, four seconds. And my brain fired back a rapid conclusion: Conservative. Probably longing for the “good old days” when white heterosexual men ruled and everyone “else” knew their place. Want to silence “the liberal media.” Would find me in my Neil deGrasse Tyson tee shirt a threat to everything they believe in.

Then I stopped and took stock of this reaction. I asked myself some version of Hillary’s Why am I feeling this way? Because I don’t think I’m like that, and I certainly don’t want to be like that, but there I was, being just like that.

So I took a deep breath, smiled at the men, and nodding at the (still) long line, said, “You think it would break the bank if they hired a few more cashiers?”

And that was all it took. We started talking about how so many big companies have made severe cutbacks in staff, and what this was doing to people’s lives.

“It’s the guys at the top, gettin’ greedy, grabbing all the money,” the younger man asserted.

“It’s the attitude everywhere now,” his uncle agreed. “I like this Bernie guy. If decent jobs and healthcare for everyone makes me a socialist, count me in.”

I wanted to hug him.

Okay, for me, that was a lucky hit. What if they had said something truly repugnant to me? Well then I would have had the option of expressing my views or walking away. But at least my response would be based on reality rather than a preconceived notion.

I know that approaching and talking to strangers is not always easy or pleasant. (I staffed a table at a farmer’s market for Elizabeth Warren during her Senate run. Trust me, I know.) But, really, how many times do we encounter someone so obnoxious that the finding of any common ground is impossible? More often, people express a mix of things—some which we connect with, others not so much. It can be uncomfortable to hear opinions and ideas different to our own, but the real world isn’t limited to three identical door colors or a single design. There are blue doors and red doors, barns door and metal doors,  French doors and glass bead curtains. And the weird, sometimes scary, sometimes wonderful, true thing is: They’re all our kind.

French doors and glass bead curtains. And the weird, sometimes scary, sometimes wonderful, true thing is: They’re all our kind.

Humans have a long history of tribalism and clannishness, but we also have a brain structure which gives us the power to evaluate our behavior and to choose to behave differently. In a world full of nuclear weapons and environmental hazards, a world facing the challenges of climate change, a refugee crisis, and cyber attacks, we can’t afford to be feuding like the Hatfields and McCoys. Each of us is depending on all of us recognizing that the sum of what we have in common is far greater than our differences.

Like the woman in the red pantsuit at the debate said: We are stronger together.