“One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken.” ~ Carl Sagan (The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark)

Recently, as I was waiting in my local hair salon, I overheard another customer ask the stylist if she had seen some issue on the news. The stylist replied that she never watched the news. “I just don’t want to know,” she said.

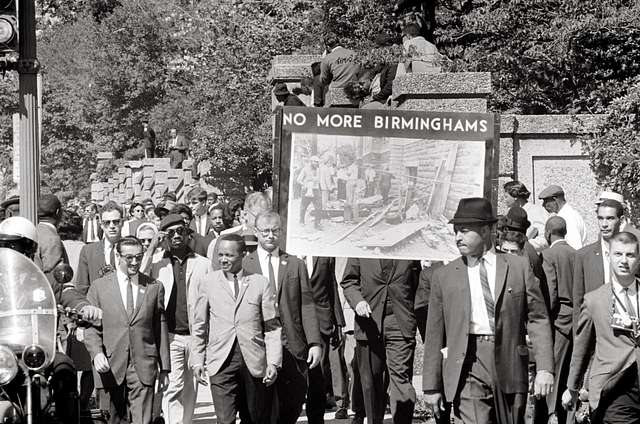

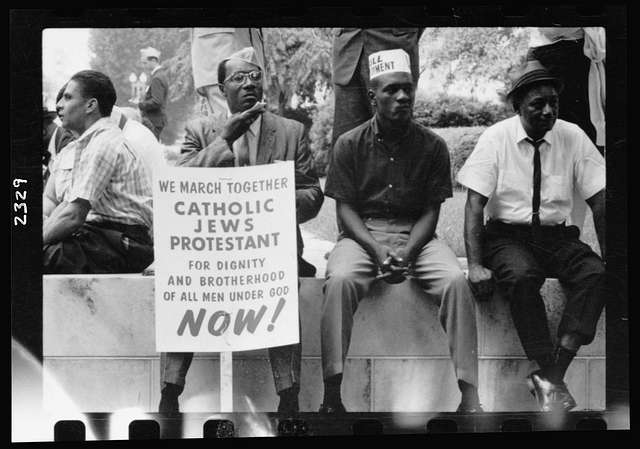

I was surprised, and distressed, by her words. Our country is at a crossroads such as we have not experienced since the Civil War. In that time, the issue was whether the union would endure. The question before us now is whether we will remain a democracy or become a dictatorship, our Constitution and fundamental civil rights consigned to the trash heap of history. None of us can afford to look away.

And yet, many of us are. Looking away. Ever since the pandemic—an event initially presided over by a MAGA-hatted president who advised us to drink bleach and who left the individual states up to their own devices when it came to procuring masks and dealing with overcrowded, understaffed hospitals as the bodies piled up in trucks during the summer of 2020—ever since then, increasing numbers of Americans have been “tuning out.”

A Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism survey reports that more than 40% of Americans say they avoid news about national politics altogether. “It’s such high stakes, no clear resolutions,” NPR’s media correspondent David Folkenflik summed up the respondents’ comments.

High stakes, indeed, in an election year. Who will we elect president and what will be the consequences? Yes, the news can often feel unnerving, even frightening at times, but we must all ask ourselves this: Do we really want to be ignorant about the people and policies that will shape our lives, our children’s lives, that will heal or destroy the environment, improve or demolish healthcare, save or terminate Social Security and Medicare, protect or outlaw our right to protest, equal treatment under the law for all Americans, access to birth control, gay marriage?

Consider the Source

“You don’t know what to believe; it’s so much information to soak in that you sometimes don’t know if it’s true or not,” one woman said in a recent Pew poll on the subject of following national politics. To be sure, the present media deluge of he said/she said/they did that/they didn’t do that can feel both confusing and exhausting So, how to choose which news to view or read?

I cannot emphasize this strongly enough: Everything has a point of view. Every newspaper article, every news broadcast, every topical book, every social media post dealing with political issues, every blog post—including this one. Think of The New York Post versus The New York Times. Or Alex Jones versus Rachel Maddow. Clearly though, while everything has a point of view, not every view is equally true, i.e., based on the facts. Toss in the nefarious strategy Trump buddy Steve Bannon calls “flooding the zone with s**t” to intentionally confuse readers/viewers/listeners, and you’ve got the perfect recipe for chaos. As Bannon bragged, “This is not about persuasion. This is about disorientation.” Beware the bamboozlers who are trying to confuse the issues—and you.

In his excellent op-ed for The Hill, Joe Ferullo, an award-winning media exec, producer and journalist who has worked for ABC, NBC and CBS, noted the steep decline in both viewership for the major nightly TV news programs and readership for print newspapers. At the same time, people are consuming ever-increasing amounts of what Ferullo calls “unpackaged” news—an endless series of unmoored headlines, updates, tweets, and notifications on their phones and tablets. A jumble of one thing after another without depth or connection. How are we to develop “a comprehensive picture of politics, the nation or the world?” Ferullo asks. Contributing to this quagmire is what CNN cites as the tendency of social media platforms to boost the “most extreme confrontational and conspiracy theorist voices.”

Sifting the Facts: Panning for Truth

Sifting what is fact versus fiction can require a little digging and cross-checking. Generally, I rely on the news agencies AP (Associated Press) and Reuters or fact-checking websites like Politifact and FactCheck.org. As an example, I’ll use an email I received yesterday from Color of Change, a self-described progressive nonprofit civil rights advocacy org. The email reported that:

Neo-segregationists have won two crucial legal victories in their fight to enshrine Jim Crow-era advantages for white people.

First, two Trump appointed judges blocked the Fearless Fund, a Black-owned venture capital firm, from issuing grants to support Black women-owned businesses. They perversely cited a Reconstruction-era law meant to protect Black people from economic discrimination. Given that Black women-owned businesses receive only 0.0006% of total funding from venture capitalists, this ruling makes it clear that neo-segregationists want to exclude Black women from access to financial resources for their businesses.”

I copied the words in bold and put them in my search bar. Up popped the AP News website where I read:

A U.S. federal court of appeals panel suspended a venture capital firm’s grant program for Black women business owners, ruling that a conservative group is likely to prevail in its lawsuit claiming that the program is discriminatory.

The ruling against the Atlanta-based Fearless Fund is another victory for conservative groups waging a sprawling legal battle against corporate diversity programs that have targeted dozens of companies and government institutions.

The case against the Fearless Fund was brought last year by the American Alliance for Equal Rights, a group led by Edward Blum, the conservative activist behind the Supreme Court case that ended affirmative action in college admissions.

Color of Change email verified! And I learned that this case was brought by the same right-wing group that spearheaded the (sadly) successful effort at the Supreme Court last June to end affirmative action in higher ed. The whole process took just three minutes. The time it takes to read and respond to one or two Facebook posts. Is the future of our democracy worth it? I think so.

Our Democracy Has Basic Rules

Contrary to what you may have heard recently from a certain orange-haired person found guilty in the first degree in a New York State trial on 34 counts of falsification of business records, the president of the United States is not above the law. Presidents cannot do whatever they want. Whenever they want. America is not a dictatorship—yet. As citizens, our best interests are served by knowing the basics of how our government works and being alert to those who would run roughshod over our Constitution and curtail our rights.

In our democracy, there are checks and balances to prevent a president from acting like a dictator: Congress, the courts. The framers of the Constitution made sure these checks were down in writing. They did not want any one person to seize power, be they king or dictator. The president cannot make new laws or change existing ones. Legislative power belongs exclusively to the House and Senate. However, in the spirit of checks and balances, the president can veto any bill they believe unconstitutional, unjust, or just plain risky.

But that’s not the end of it. The president’s veto cannot simply amend or alter the proposed legislation. Instead, the president’s objections are sent back to the House or Senate (depending on which branch of Congress originated the legislation) where the bill will be reconsidered. If two-thirds of that body still agree to pass the bill as written, it is sent to the other house for the same process. And if two-thirds of that house still approve the bill it becomes law. This is spelled out clearly in Article I, Section 7, clause 2 of the Constitution. This procedure prevents Congress, as well as the president, from seizing total power. No dictators whether on “Day 1” or “Only on Day 1.”

What a President Can Do

Reading across a wide array of Internet articles, I repeatedly came across reports of undecided voters leaning toward Trump because they blamed Biden for the sharp uptick in the cost of groceries and other consumer goods. Okay, first of all, I travel outside the U.S. each year. Prices are up everywhere. Second, the leap in prices began soaring as COVID gripped the country in early 2020, well before Biden was elected. Supply chain issues and so forth, companies said. Once Biden took office in 2021 and got the plague under control with his vaccine roll-out, companies saw no reason to yield the big profits they’d been enjoying. Third, and most important, in a democracy, in a capitalist country, the president cannot unilaterally lower costs. They cannot simply order private companies to drop their prices.

What a president can do is propose legislation. They can urge Congress to enact it into law, but that’s the limit. The president cannot introduce it in the House or Senate. Biden’s Build Back Better Act was introduced into the House by Rep. John Yarmuth (D-KY) in September 2021 and passed by that body in November. Described by Arvind Ganesan, business and human rights director for Human Rights Watch, as legislation that “could help reverse decades of underinvestment in social protection”, the Build Back Better Act included major investments in free universal pre-school and the highly popular child tax credits, affordable housing, expanded healthcare, the right to four weeks of paid leave, and increased penalties for workplace safety violations or violation of workers’ right to unionize. The icing on top was $555 billion to fight climate change and authorizing Medicare to negotiate prices for a lengthy list of prescription drugs. In a Senate split 50/50 between the two parties, and no Republicans willing to vote for the bill, it would take every Democrat with VP Kamala Harris breaking the tie, to pass the act. That’s when Sen. Joe Mansion, a Dem in name only, announced he would not vote for the bill as written.

A much-watered-down version The Inflation Reduction Act was passed into law in 2022. The new bill retained the funds for healthcare, a 15% minimum corporate income tax, and record spending for climate (though substantially less than the initial bill), but the right of Medicare to negotiate drug prices was immediately contested by pharmaceutical giants Johnson & Johnson and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among others, who currently have lawsuits pending against Biden’s Health and Human Services Department to stop the negotiations.

Undaunted, Biden has continued to press for more and better, asking Congress last March to increase the number of prescription drugs Medicare may negotiate from 20 to 50 per year. His proposed budget for FY2025 would expand Medicare’s $2,000 annual out-of-pocket limit on drug costs to people of all ages with private insurance. In June, Biden announced he is forming a “Strike Force on Unfair and Illegal Pricing” to be co-chaired by the Federal Trade Commission and the DOJ to investigate and stop illegal corporate price-gouging practices in groceries, housing, healthcare and financial services that hurt or cheat American families. This is what a president can do and Biden is doing it.

Ignorance is Not Bliss

The need to protect their mental health was a reason cited by many respondents in the Pew poll of people who have largely or completely tuned out of national politics and the news. Others expressed frustration over the two-party system. “I hate the fact that you’re forced to pick between the lesser of two evils when voting. No, I don’t want either of them. Next,” a man in his twenties complained.

However much one agrees or disagrees with that man’s feelings, the bottom line is one of the two major candidates, Biden or Trump, will remain or become president in November. The four other candidates—Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., an outspoken anti-vaxxer whose legendary family has disavowed him and publicly supports Biden, is running as an independent, as is activist Cornel Wes, along with the Green Party’s Jill Stein, and the Libertarian Party’s Chase Oliver—combined will only draw a few percentage points of the vote, but possibly just enough to swing it one way or the other for Biden or Trump, as Jill Stein’s candidacy may have done for Trump in 2016.

As for “protecting one’s mental health”, I don’t buy it that tuning out stops the worrying. The hair stylist I mentioned at the outset? She’s still depressed, worried, agitated. Ignoring what’s happening around you, the threats our country and our world faces—it doesn’t bring inner peace. The body still remains stressed, the mind exhausted with the great effort to silence what is occurring out there.

Engaging with the world, taking positive action for the outcomes you wish to see—I know from experience that can help and it can make a difference. In 2020, I wrote 250 postcards to Georgia voters to help elect U.S. Senate candidates Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock. They both won their seats. Of course, 250 postcards was a drop in the bucket but when all the “drops” were combined—the efforts of all my fellow postcard writers—it was enough. Likewise, if we close our eyes and ears to what’s happening in the moment, what’s at stake, our failure to engage may be enough to bring about the dark future we fear.

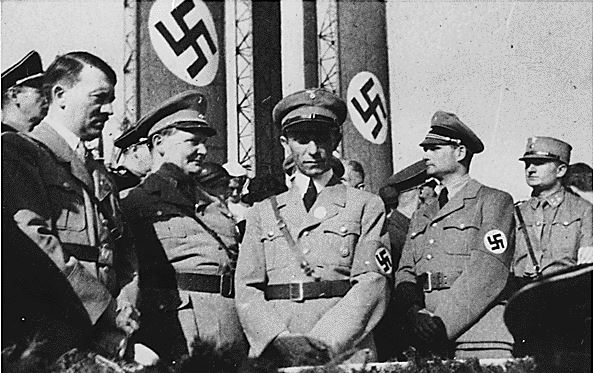

In this critical moment, it’s worth remembering that when Hitler seized control of the German government in 1934 and began his “make Germany pure again” program—rounding up and exterminating the Jews, Communists, trade unionists, Black people, Roma people, gays, the mentally- and physically-challenged—many “good Germans” said, “It doesn’t affect me. I’m not in any of those groups,” and looked the other way. They couldn’t have been more mistaken. Eleven years later, when Germany finally surrendered to the Allies, Hitler had fomented a world war that killed nearly 60 million people, including six million Jews, and decimated his own country.

However distressing it is to see what’s happening in the world now, it is nothing compared to the disaster that awaits us if we close our eyes.

People speak of life passing you by, but our digital addictions are causing us to pass by life without pausing to register its pulse. Texting. Tweeting. And then there’s selfie-madness.

People speak of life passing you by, but our digital addictions are causing us to pass by life without pausing to register its pulse. Texting. Tweeting. And then there’s selfie-madness.