When the films Oppenheimer and Barbie both opened on July 21, I felt a surge of joy and hope. Joy that big-screen films may have survived both the plague and the surfeit of made-for-TV movies streaming in its wake. Hope that the return of such films, bringing us together again in movie theatres large and small across the country—happily munching popcorn, laughing together, crying together, sitting on the edge of our seats as the tension mounts—will mark the beginning of a return to shared cultural experiences. We. Need. This.

For too long now, we’ve been asunder. Pawns in a game of divide-and-conquer that’s been creeping up on us for almost three decades. (More on this in a moment.) Gen Z has never experienced an America that is not riven “twenty ways to Sunday” as my mom used to say. Has never known a United States.

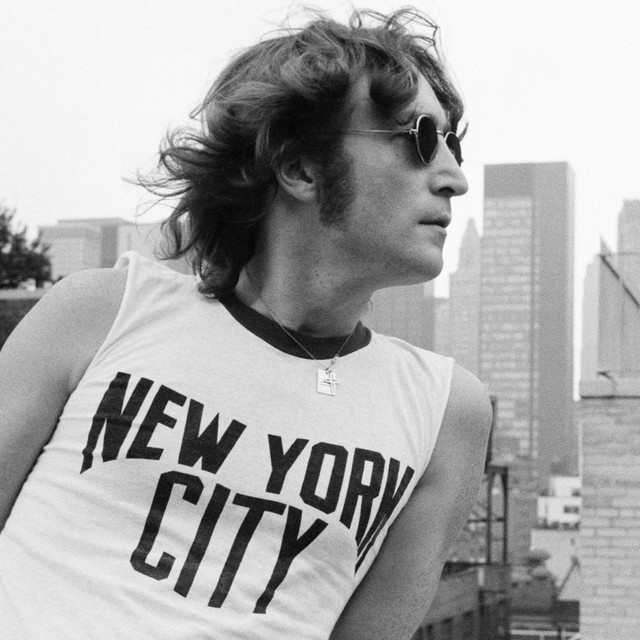

To say this is not to wax nostalgic for some lost idyllic democracy of yore. Our American “melting pot” has always struggled to meld. Has always fallen far short of a true integration of all peoples when it comes to equal opportunities in education, housing, employment, health, and rights. But our shared American culture—movies, music, TV shows, news broadcasts—meant we all listened and danced to the songs of Motown, Queen, Little Richard, the Beatles. We all watched Saturday Night Live, Star Trek, All in the Family. We all saw Titanic, The Godfather, Men in Black. We all got our news from one of three network sources—ABC, NBC, CBS—each barely distinguishable from the others. We all tuned into the impeachment proceedings against Nixon in the wake of the Watergate scandal. And we all witnessed Neil Armstrong stepping onto the Moon in July 1969—“That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” These commonalities helped forge a coherent society. An us.

Raising America’s Collective Conscience: How A Free Press Challenged Us To Be Better

Those cultural bonds also challenged us to look at ourselves. Not just our neighborhood, or even our region, but our entire country. This vast entity called America—who were we? In 1960, our thousands of local and big city newspapers, together with our local and network news stations, all brought the story of Ruby Bridges into our living rooms, as the six-year-old, flanked by federal agents, entered her new school in Louisiana, the first Black child to integrate an all-white school in the South. Three years later, we all saw and heard Martin Luther King, Jr. deliver his “I Have A Dream” speech at The March On Washington.

Those widely-shared stories and images awakened many white Americans to the deep injustices that Blacks Americans continued to suffer, and created a vast support network across the country for the Civil Rights Movement. Freedom Riders—Black and white civil rights activists together—boarded interstate buses in 1961 and rode into the Deep South to challenge Jim Crow segregation. Four years later, the nationally-televised Selma to Montgomery marches in Alabama showed Americans everywhere just how brutal southern resistance to integration was, as we watched Alabama state troopers beat and gas Black activist John Lewis on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, a day that would become known as “Bloody Sunday” in the struggle for civil rights. [Lewis would go on to become the U.S. representative for Georgia’s 5th district, a position he held for 33 years until his death in 2020.] The nationwide televising and reporting of these events not only raised America’s consciousness. They led to the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both signed into law by President Johnson.

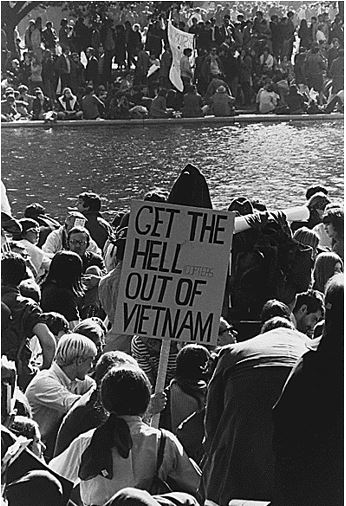

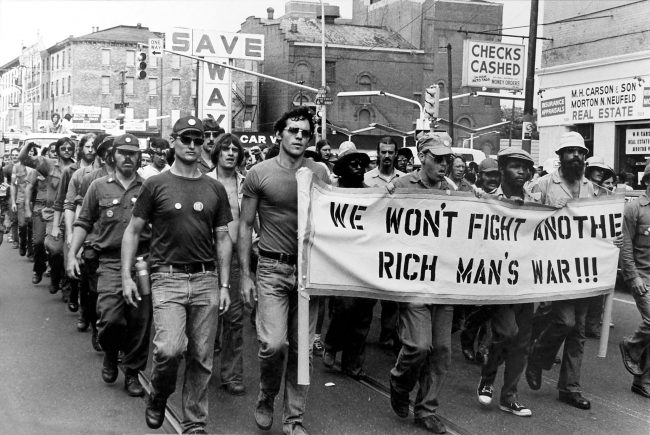

News broadcasts and newspapers also brought the escalation of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War into our living rooms on a nightly basis, spawning an active anti-war movement in America that numbered in the tens of millions and defined a generation. Life magazine’s cover story on the 1968 My Lai Massacre in Vietnam further galvanized American support for ending that war. Life was another touchpoint of American culture.

That we all experienced the same cultural and political events does not mean we all held hands and danced around a maypole in some idyllic Shangri-la. There is no movie or TV show, no song, no social movement, no political moment that will bring us all into agreement. There always has been and always will be differing tastes, opposing opinions, and just plain bad actors who need to be dealt with—in a non-violent legal framework—when they cross the line. But I would argue this underscores all the more the desperate need for shared cultural experiences through which we can relate to others and build bonds.

Sowing Division: The Rise of Fact-free News and the Silencing of Voices

So, what do we have now, in this brave new world?

We have Fox News (which first aired in 1996) and One America News (oh, the irony of that name!), and Breitbart News and QAnon lunacy, all lying to us, dividing us by intent, shaping our worldview to suit their own ends. Ends antithetical to democracy itself.

We have a press that has shrunk—and continues to shrink—at an alarming rate. A recent study by Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, and Integrated Marketing Communications found that, on average, two papers go out of business every week in the U.S. In the past 18 years, more than 2,500 have ceased publishing. “This is a crisis for our democracy and our society,” stated Penelope Muse Abernathy, lead author on the study.

We have a Supreme Court, the majority of which has been carefully selected and, in some cases, bribed by billionaires to dismantle our rights, hence, our democracy. Even before they struck down women’s right to abortion and affirmative action in education, SCOTUS was hot on the trail of curtailing our civil rights. In Citizens United (2010), the Court claimed that corporations were “people”, reversing longtime campaign finance restrictions to allow corporations and other outside groups to spend unlimited amounts of money on elections. Three years later, the Court ruled in favor of officials from Shelby County, Alabama, gutting a key part of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. President Obama lamented the decision, saying it invalidated core provisions of the law, upsetting “decades of well-established practices that help make sure voting is fair, especially in places where voting discrimination has been historically prevalent.”

What happened to a nation who rejected Jim Crow? A people who rose up and stopped an unjust war? Who grooved together to the Temptations’ My Girl and laughed together watching Beverly Hills Cop at their local cineplex?

One is the Loneliest Number

Polls suggest that nation is still out there. Seventy percent of likely voters support the Freedom to Vote Act—a majority support that extends across party lines. In a May 2023 Gallup poll, 85% of Americans said abortion should be legal in at least some circumstances. So why has our collective voice been reduced to a whimper? Why has our cultural cohesion become invisible? Why do so many of us stare at each other with suspicion—or fear?

For too long, we have been isolated, each in our own little bubble. Individually streaming our movies for consumption at home, causing nearly a quarter of America’s indoor cinemas to shutter their doors from 1995 to 2020. And that’s before the pandemic hit.

We individually stream our tunes, too. Music streaming services have revolutionized the way we listen to music, the CEO of Media Music News posted Linked In. They certainly have. From Spotify and Pandora to YouTube and Big R Radio Network (this last, features more than three dozen channels, including something called Yacht Rock, Country Oldies, Post Grunge Rock, and Explicit Top 40), we select our music like menu items at a restaurant, according to our individual taste. But if we always order the Bolognese, how are we gonna know what we might be missing with the Tandoori chicken or the Kung Pao tofu? How can individual streaming provide the kind of social glue that connects us from coast to coast as jazz did in the 1920s, as swing and Big Band did in the 1940s, as rock, blues and soul did in the 1960s, as New Wave, Hip-Hop, and punk rock did in the 1980s?

While it’s true that radio has been diversifying (rock/country/classical) since the 1960s, radio was then and continued to be, until the turn of the millennium, the way America sampled new music, shared tunes, forged a common culture. As Soul Source notes: DJs on “pop stations would pick many soul sides to spins…even when many of the other things given heavy airplay on their station were by…the Beach Boys, the Beatles, the Monkees, Bobby Vee, the Lovin’ Spoonful, Frank Sinatra.” Now if that ain’t a diverse playlist, I don’t know what is. And from my own experience, I can attest that country singers like Kenny Rogers, Glen Campbell, and Dolly Parton were heard on pop/rock stations everywhere. Casey Kasem’s American Top 40 Countdown was a coast-to-coast weekly radio show. “Listening to Casey was as much of a family Sunday tradition as going to church,” Remind Magazine says, featuring the “best-selling and most-played songs from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from Canada to Mexico[emphasis, mine].” A Top 40 for America.

This hermetic existence many of us are now living—plugged into our personal devices, sealed off from society and our fellow beings—has made for a lonely country and a sad, scared, increasingly-violent people. A divided people easily manipulated by those who know the buttons to press—racism, homo- and trans-phobia, religion—to gain their own ends: a dictatorship of the rich. Can our democracy with all its flaws, but still far superior to a fascist oligarchy, survive these divisions?

Commonweal: Reclaiming Our Cultural Cohesion

So, that is why I celebrate the opening of major, wide-audience films like Barbie and Oppenheimer. In New York City, I saw groups of children in pink gear, romping noisily together after seeing Barbie, elated at sharing an experience with their peers, something they were denied during the pandemic’s grueling loneliness of online-learning. Why I, who am not an early-morning person, willingly got up at 5:30 a.m. to be on line, literally, by 7:00 in Central Park, with hundreds of other theater buffs, waiting for tickets to Shakespeare in the Park’s production of Hamlet. Tickets that are free to the public for an event in a public space. Why I smile every time I pass my neighbor Louisa’s house with the HELLO sign posted prominently by her front door—a sign, a word, that welcomes and embraces all who pass by.

I will close with something a friend shared recently on Facebook. It was signed by Ira Byock, a palliative care physician and author. The journalist in me dug around to find its source. Though I cannot definitively say Mead told this exact story, I can tell you it has been widely quoted. And for my purposes here, it is the story itself that matters:

Anthropologist Margaret Mead was asked by a student what she considered to be the first sign of civilization in a culture.

Mead said that the first sign of civilization in an ancient culture was a femur (thighbone) that had been broken and then healed.

Mead explained that in the animal kingdom, if you break your leg, you die. You cannot run from danger, get to the river for a drink or hunt for food. You are meat for prowling beasts. No animal survives a broken leg long enough for the bone to heal.

A broken femur that has healed is evidence that someone has taken time to stay with the one who fell, has bound up the wound, has carried the person to safety and has tended the person through recovery.

Helping someone else through difficulty is where civilization starts. We are at our best when we serve others.

Be civilized.

To that, I can only add my conviction that civilization begins, is nurtured by, survives through what we share in common. A culture open to and embracing all.