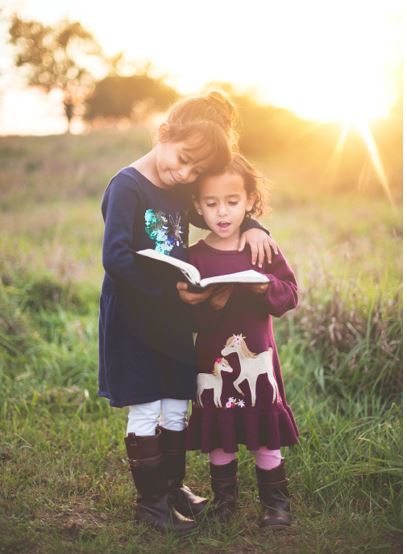

Bless the beasts and the children, for in this world they have no voice, they have no choice. (DeVorzon/Botkin)

I was sitting on my side porch the other day when my neighbor’s cat, Binks, came tearing up the driveway. Usually, Binks ambles over for a visit, a head rub, rolls fetchingly on his back for a belly massage. Not today. Today he was freaked, for right behind him a girl of about nine raced up the drive on her bike, tossing handfuls of pebbles and acorns at poor Binks.

I leapt up instantly. “Stop that right now! It’s not okay to throw things at animals!” The girl, startled by my appearance—my Subaru had obscured me from her view—stammered, “Okay,” and fled across the street, back to the safety of her friend, a boy about seven. For several minutes they threw the stone/seed mixture at nothing. I settled back on the porch.

“I saw this really funny kid video,” the boy said to the girl. “A kid shoots his mom in the back with a really strong nerve gun—you know, the kind that gets you good. And she’s on a ladder painting, so when the gun hits her, she falls backward off the ladder and the paint goes all over her.” The kids laughed and then pedaled off down the street. I continued my surveillance until I was sure they were gone. What remained was my disturbance. A really funny kid video?

You Are What You Eat: Growing Up On A Steady Diet of Violence

A second troubling incident occurred during my daily ramble—a walk that takes me through the ordinarily peaceful streets bordering on the local college campus. On the front porch of one house, a woman was sitting with her two boys, ages about six and eight. I’d seen the kids many times, playing in the yard. That day, however, the boys were busily engaged in opening two large packages that had just arrived. The older one let out a whoop and held up the contents—two AR-15s, toys I think, at least I hope they weren’t real, but with Marjorie Taylor-Greene pushing guns for kids, one can’t be certain. I mean, there are gun manufacturers out there aggressively marketing real firearms for children. Just google “real guns for kids” and you’ll get an eyeful. Top Five Handguns for Kids; How to Choose Your Child’s First Gun; Feels like Mom and Dad’s Gun: U.S. Firm Makes Real Rifles for Children.

The older boy immediately struck a pose with his AR-15, chillingly familiar from news videos of violence around the globe—Iraq, Yemen, Syria, Palestine, Israel, not to mention the endless mass shootings at U.S. schools, shopping malls, and public events like the Harvest Festival in Las Vegas where more than a thousand bullets were fired, killing 60 people and wounding another 400. That last event occurred in 2017, and people began to talk about a time coming when mass shootings would be a daily occurrence in America. Well, we’ve crossed that threshold and left it in the dust. By September 3rd of this year, the U.S. had already clocked 484 mass shootings for 2023.

And kids see it all. Even if a parent monitors TV consumption of violence at home, it’s everywhere. As Common Sense Media warns: Thanks to live-streaming apps… kids can watch actual scenes of real-life violence in their social media and news feeds. They can also interact with it, and they do… commenting, sharing, and using other digital tools to process the raw footage. In one particularly harrowing instance in 2016, a young French woman talked about her sadness and suicidal thoughts. Viewers are said to have encouraged her to do the deed—which she then did by throwing herself under a train. In that same year, an Ohio couple was arrested. The man, age 29, was charged with raping the underage friend of his 18-year-old girlfriend—with his girlfriend’s consent, making her an accomplice as she was the one livestreaming the rape on Periscope. In court, it was revealed that the girlfriend had gotten carried away, giggling in her excitement over the number of “likes” she was getting as she filmed the crime.

Children’s constant exposure to horrific real-life violence and tragedy is not just a problem for those adults currently raising kids. It’s a problem for everyone. It’s our problem. At a time when many states are hollering about the need to crush “woke” agendas in schools that focus on teaching children respect for others and fostering communal empathy, it seems to me we have never been in greater need of peace, love, and understanding.

Dumbing Down the Content and Ratcheting Up the Fascism

What we are getting instead is book bans and radical-right educational agendas, like the videos from unaccredited PragerU that tell children slavery was a good thing for Black people, or at least it wasn’t that bad—better than being killed; that climate change is a bunch of hokum; and (my favorite) that Jesus—who, as Vanity Fair’s Caleb Ecarma points out, predated Adam Smith by more than a millennium—was a free market capitalist.

See an agenda here? Co-founded by conservative talk-radio host, Dennis Prager, and financed by fracking billionaires Dan and Farris Wilks (as well as the Betsy DeVos family and others of that ilk), PragerU has no ties to any accredited educational institution. Its CEO, Marissa Streit claims accreditation “these days is synonymous with controlled [by ‘political elites’].” Much of PragerU’s “curriculum” consists of short videos for grades 6-12 on political and social issues: “Social Justice Isn’t Justice.” “Make Men Masculine Again.” “Income Inequality is Good.” “The Inconvenient Truth About the Democratic Party.”

If you think such materials are B.S., but they’re not teaching our kids it’s okay to throw stones at cats, I encourage you to think again. With a “curriculum” that devalues Black people, indigenous people, gay and trans folks, women, and the poor, what chance do animals have?

As of this writing, Florida has approved PragerU curricula for use in schools across the state. Oklahoma’s State Superintendent of Schools has okayed PragerU videos as “supplemental curriculum,” and New Hampshire’s Board of Education recently voted to adopt one PragerU course on “financial literacy” for its secondary schools. Digging around the Net, I was heartened to discover that these approvals have been met with pushback from many districts in the three states. But history teaches us that what is “optional” or “supplemental” today may well become mandated tomorrow. That any of our children are being exposed to this far-right anti-science, anti-democratic propaganda should concern all of us. PragerU and its “curriculum” are much more than the absence of education; they are indoctrination with a bullet. An agenda that panders to the Christian nationalists and is financed by the uber rich.

Thought Control: The War on Books

According to Pen America, there have been more than 6,000 book bans in the U.S. in the past two years. Two of the biggest targets—surprise, not—are books that feature characters of color or deal with issues of race, and books with LGBTQ+ characters. Perhaps most important to note is that virtually all of the 2,532 book bans in public school libraries in the past year jettisoned the “proper review process by a committee of educators and librarians.”

It’s easy to dismiss these bans as the megalomaniacal crusade of a few fanatics and extremist cranks, largely limited to far-right states like Florida and Texas. But the numbers keep rising, as do the list of states afflicted. Missouri, Utah, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Michigan, North Dakota, Virginia, California—all have seen a significant jump in book bans this year. Even bluer-than-blue Massachusetts is not exempt. According to ACLU Massachusetts, the state saw 45 attempts to restrict access to books last year.

And what are these “offensive” titles, these books so “threatening” to our youth that they demand removal from school library shelves? Among the banned are Pulitzer Prize-winner, Maus, the story of author Art Spiegelman’s father’s experiences in the Holocaust (which the Wall Street Journal, hardly a bastion of “woke”, called the most affecting and successful narrative ever done about the Holocaust). Verboten, too, is Newberry Honor winner The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963, Christopher Paul’s tale of a Black family who journey from Michigan to Alabama to visit Grandma and run smack into the Civil Rights Movement where one of the family narrowly escapes death in the Birmingham Church Bombing. Prominent among the book’s themes are kindness and compassion. Well, we certainly don’t want those “liberal elite” values being taught to our kids.

But it seems we do. A 2022 American Library Association poll found that more than 70% of parents are opposed to book bans. That’s a sizeable majority. So just who are these book-banning fanatics intent on taking away our children’s freedom to read? According to Suzanne Nossel, CEO of PEN America, the current onslaught of book bans “represents a coordinated campaign…being waged by sophisticated, ideological and well-resourced advocacy organizations.” PEN has identified at least 50 groups who aggressively advocate for banning books in our public schools. Prominent among them is Moms for Liberty, a right-wing group who started in Florida in 2021 and has since sprouted 278 chapters across forty-five states. Last time I counted, that is most of America. How has a group that in no way represents what most Americans want or believe spread so rapidly and far? I’ll give you a hint: The reason begins with m and ends with y.

No Time for Learning: The End of Literature?

The war on public schools being waged by the far right and the onslaught of book bans—as heinous as they are—are not the only threats to our children’s education and development. For the past twenty years, the pressure of high-stakes testing, beginning in elementary school, has forced many educators to “teach to the test.” Whether it was called the No Child Left Behind Act (2002) or its revamp, the Every Child Succeeds Act (2015), in practical terms the intense focus on standardized testing in our public schools (with the results often tied to federal funding and teachers’ salaries) has led to a time crunch in the classroom. Teachers across the nation complain they must sacrifice reading entire works of literature to focus on those “bits and pieces of books” that will get the kids through the tests. They fear that reading, once a cherished pleasure, has become a loathsome chore. Readicide, as English educator, Kelly Gallagher, calls it.

How is a student to “analyze how and why individuals, events, or ideas develop and interact over the course of a text”—an essential skill every citizen needs to understand and evaluate our world, and a key standard in English Language Arts—if all they receive are disconnected passages from A Tale of Two Cities or The Grapes of Wrath or Romeo and Juliet (removed in numerous Florida school libraries—“too sexy”)?

The Kids Are Not Alright

Education should prepare our children for the world they are inheriting—it’s history, its present, its future. Today’s kids are facing incredible challenges on multiple fronts—environmental disasters; real threats to drinkable water, breathable air, and the global availability of food; the trend toward fascism around the world with its rising tensions and the resultant hostilities that threaten nuclear war. We desperately need thinking human beings. And right now, many of our kids are crashing and burning.

The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) 2022 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report warns us that: Nearly 20% of children and young people ages 3-17 in the United States have a mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral disorder, and suicidal behaviors among high school students increased more than 40% in the decade before 2019. Mental health challenges were the leading cause of death and disability in this age group.

The report also cites a study conducted by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) that shows the number of children ages 3-17 years diagnosed with depression grew by 27% between 2016 and 2020.

Little kids, depressed? Rapidly increasing numbers of middle- and high-school students, anxious to end it all? We should be outraged at these findings. More important, we should be doing something to stop this assault on our kids, our country, our world.

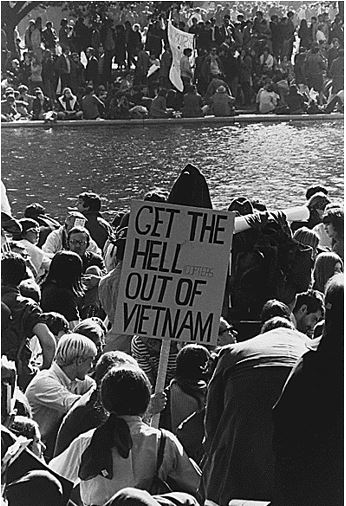

Who’s Fighting Back

The war against education, against freedom of thought, against democracy itself is not going unchallenged. In June, Governor Pritzker (D) of Illinois signed a bill into law that will withhold state funding from any public library that removes materials because of “partisan or doctrinal” complaints. “Young people shouldn’t be kept from learning about the realities of our world,” Pritzger said. “I want them to become critical thinkers.”

California’s Governor Newsom (D), Attorney General Banta and State Superintendent Thurmond teamed up to write a joint letter warning the state’s educators against pulling books from library shelves. Doing so, they said, may qualify as “unlawful discrimination,” and expose the perpetrators to an examination by the state’s Attorney General’s office. Several cases have already come to the state’s attention—one involving rejection of a social studies curriculum that includes gay rights—and are being aggressively pursued.

Nine states—New Jersey, Illinois, Delaware, Massachusetts, New York, Maryland, New Mexico, Washington, Rhode Island—and the U.S, Virgin Islands have signed a letter to textbook publishers expressing their dismay that some publishers are reportedly “yielding to…government representatives calling for the censorship of school educational materials.” The states are demanding that publishers “hold the line for our democracy.”

The National Campaign for Justice reports that Senator Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) and Representative Jamie Raskin (D-Maryland) have introduced a bill to stop book bans and defend the freedom to read. Fifty-two co-sponsors from the House and twenty senators have already taken up the fight.

If Not Now, When? If Not Us, Who?

When I was studying for my M.Ed. in 2000, Alfie Kohn, renowned lecturer and author on education (The Schools Our Children Deserve and What Does It Mean To Be Well Educated? among other titles), spoke at the University of Massachusetts. He was addressing the distress many teachers, parents, and kids were feeling about the state’s new MCAS tests to be administered in grades 4, 8, and 10—the final test to determine whether one graduated. Teachers were up in arms—they saw the writing on the wall: Teach to the test!—and many fourth grade teachers resigned in protest. Parents worried that their children, particularly those with special learning needs, would be traumatized by the pressure and fear of failure. Kohn, with his solid background in social science research and best educational practices, advised the packed auditorium: From wherever you stand—school administrator, educator, parent—you must fight this. Be the link in the chain of resistance that will not break.

And here we are, two decades along, but finally a ballot initiative has been filed with the Massachusetts attorney general that would end the MCAS as a requirement for graduation. President of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, Max Page, explains his union’s strong support for the initiative: “All the focused test prep…all the time wasted preparing for this test, has not had the impact …‘ed reformers’ want. It’s time now to change it.”

All the time wasted… Yes, twenty years is a long time. But if we never start fighting to reclaim our kids’ future, our democracy, we will never win. Child labor laws have been scuttled or relaxed in Arkansas, Iowa, New Jersey and New Hampshire. More than a dozen other states are attempting to do the same. Many Republican candidates speak openly of abolishing the Department of Education if they are elected, calling it “a prime example of Washington’s meddling in American lives.” The agenda couldn’t be clearer: a Christian nationalist education for the well-to-do and forced labor for the rest of our kids. (Recall the PragerU video, “Income Inequality is Good.”)

Yes, eternal vigilance is the price of liberty. In this moment, vigilance means voting this November 7. It’s true, there’s no “big” names on the ballots in 2023. But there are state board of education members and—depending on where you live—governors, attorneys-general, secretaries of state. There are statewide and local ballot measures. In many communities, there are elections for local schoolboard members. Please don’t sit home because it’s an “off year” election. When we don’t decide our future, someone else will always step in and decide it for us. In these times, there are a lot of dangerous people, backed by big $$$ donors, all too willing to do that.

The Washington Post is famous for its slogan Democracy Dies in Darkness, an allusion to the silencing of the press. But I would argue that the first threats to democracy are always made in plain sight for all to see. We are there. We must act now. Fight back. Protest. Vote.