In 1970, Alvin Toffler published a little book that rocked the world: Future Shock. As we passed from an industrial to a “super-industrial” society, he predicted, change would no longer be the steady plodder it had been, but an exponentially increasing cruise missile. People would be left feeling disconnected and stressed out—wandering disoriented like victims of a bad hangover.

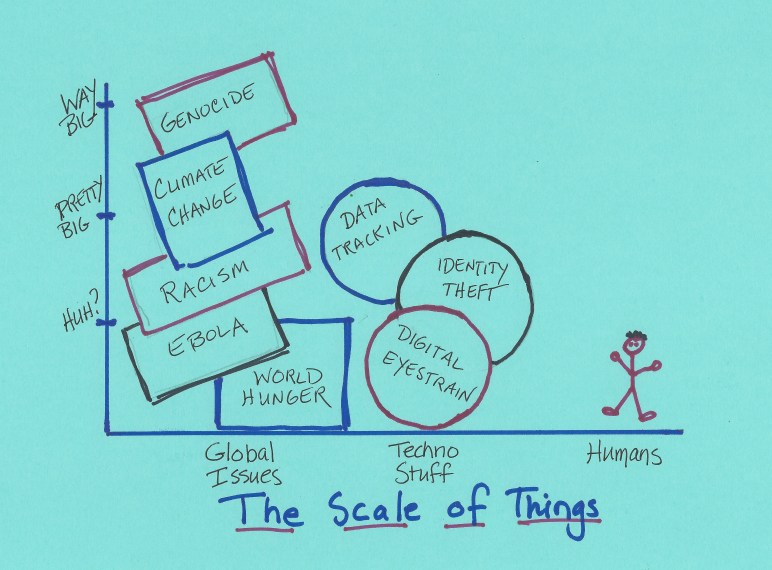

As is true for all restless, brilliant people who peer into the future (Orwell, Marx), Toffler got some of it right and some of it wrong, But he was dead on about the shock we would get from the rapid, large-scale technological and social changes we face today. We find ourselves in a world that has completely outstripped the human scale. We want to act, but how? Where to start? If you’ve ever tried to straighten out a problem with Google, you know exactly what I mean. It’s like that moment in Paddy Chayefsky’s Network where thousands of New Yorkers open their windows and shout, “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore!” But the question is: Who’s listening?

“The average individual knows little and cares less about the cycle of technological innovation or the relationship between knowledge-acquisition and the rate of change. He is, on the other hand, keenly aware of the pace of his own life—whatever that pace may be.”

Toffler Alvin. Future Shock. 1970.

Some years ago, I moved into a house across from the Quabbin Reservoir, a massive water supply source for Boston that was built in the 1930s, forcing the inhabitants of four communities from their homes. I did a lot of research on the subject for a piece I was writing at the time. It reminded me that throughout much of human history, the most common experience was to be born, grow up, and die in one place. This certainly has its drawbacks, but it also provides people with an identity, a stable community, and lifelong friends—three basic human needs that are currently on the endangered list.

In those Quabbin towns, you were a known quantity to your neighbors and they to you. You were also likely a butcher, a baker, a candlestick maker. You did work you could accomplish with your own hands, the rewards of which were tangible and immediate. You planted tomatoes, you tended tomatoes, you harvested tomatoes, you ate tomatoes—or sold them at your local fresh air market. If carpentry was your thing, you bought the boards from your friend who owned the local sawmill, spent some days sanding, fitting, joining, and varnishing. Then you sold the finished product–a dresser, a cupboard–to your neighbor across the meadow. That’s human scale.

Many of our surnames also reflect our ancestors’ connection to their work. Names such as Smith, Wainwright, Baker, Funar (Romanian: rope maker), and Bagni (Italian for public bath house attendant—love that one) once told people who you were. If this naming principle applied today, who would we be? Mr. Clouddeveloper? Ms. Derivatives? Weirdly enough, we have invented a world where we feel small and indistinct. A global society where corporations are people, and people are non-entities: consumers, website clicks, data points on an algorithm.

This devaluation of human beings has its roots in the industrial revolution. I mentioned Marx at the beginning of this post. The thing that stuck with me most from Das Kapital was the example of the guy who worked at a spinning machine in a factory. The man worked the machine, a treadle affair, with his right hand and foot. Until some bright boy of industry came up with this idea: If spinners can produce X amount of yarn in twelve hours with one hand and one foot, they could produce 2X that amount if they worked a second machine with their left hand and foot. It had everything to do with expanding profit margins and nothing to do with people. I’ll cut to the chase: Marx’s poor spinner went bonkers. People have limits. They grow tired. They get frightened. They waver, uncertain. They require tenderness. This is not a sign of redundancy. It is the sine qua non of our humanness.

This devaluation of human beings has its roots in the industrial revolution. I mentioned Marx at the beginning of this post. The thing that stuck with me most from Das Kapital was the example of the guy who worked at a spinning machine in a factory. The man worked the machine, a treadle affair, with his right hand and foot. Until some bright boy of industry came up with this idea: If spinners can produce X amount of yarn in twelve hours with one hand and one foot, they could produce 2X that amount if they worked a second machine with their left hand and foot. It had everything to do with expanding profit margins and nothing to do with people. I’ll cut to the chase: Marx’s poor spinner went bonkers. People have limits. They grow tired. They get frightened. They waver, uncertain. They require tenderness. This is not a sign of redundancy. It is the sine qua non of our humanness.

Recently, there’s been a lot of whining about our “age of narcissism,” evidenced supposedly by the craze for “selfies” and a surfeit of oversized egos who (how dare they!) demand to be respected as people. I admit, the guy with the selfie-stick in Florence got on my nerves a bit, as he filmed himself prattling about every place he was walking away from. But, I think the narcissism-cops may be missing a crucial point. What if all those selfies are a validation: “I’m still here!” What if the Facebook posts and the Tweets are really a cry: “I’m a person. I need to be known.” What if those “egotists” insisting on respect for their personhood have got it . . . exactly right?

I don’t buy that we’re a narcissistic or apathetic lot. I think it’s just that we often feel like we’re on a treadmill without a pause button. We can’t even slow the speed. I go to my local supermarket. I check out through an automated line. At the bank, a machine swallows my paycheck, then regurgitates my cash. I try to make a $10 online donation for Syrian refugees. I get rejected because there’s a $5 minimum. (I know—this doesn’t make sense.) I hit the “contact us” button. A form pops up, but it’s impervious to all my attempts to enter my info. In frustration, I try the e-mail reply button, and type a detailed message to someone named Ken. I never hear from Ken.

Globalization certainly offers a lot of positives. People like Malala Yousafzai have a world stage to champion human rights and female education. Rapid response to hurricanes and other natural disasters, made possible by computer technologies, brings life-saving aid to millions. But global awareness also brings everything rushing in—the painful plight of Syrian refugees, mass shootings, the melting of the Arctic ice cap—like some mad tidal wave. As we struggle to swim faster and faster, post-modern life can feel a lot like drowning. Not being able to address everything can wind up making us feel we can effect nothing. In this vast world, spinning at digital speed, all we have is our humanity. And each other. But if anything can save us, it will be exactly that. We can each do some one thing, one piece of meaningful work to reclaim our world. Together, we can do many things. In the spirit of Steve McQueen’s Papillon, we must link arms as we jump into the swirling waters of this crazy planet, and affirm, in unison, “We’re still here!” That will, indeed, be a brave, new, human world.