Hundreds, if not thousands, of books have been written on the subject of Time—what it is, how we perceive it, how to manage it. From Einstein’s Relativity: The Special and the General Theory to Kevin Kruse’s 15 Secrets Successful People Know About Time Management, time—that elusive thing that keeps on ticking, ticking, ticking—continues to baffle us.

But for my money, no one has captured the truth of the matter better than James Baldwin, American writer and civil rights activist, who said: There is never a time in the future in which we will work out our salvation. The challenge is in the moment; the time is always now. As much as we duck and dodge, delay and defer—time for that later, once everything is settled, when I feel less harried—there’s no denying Baldwin nailed it. Tomorrow never comes. It is always now. Now is the time.

Say It Now

One of the most tragic figures to ever grace the literary world is the poet Sylvia Plath. Plath’s Ariel, a collection of poetry written in the last months of her life, would rock the world and catch fire with the burgeoning women’s movement of the 1960s. Her novel, The Bell Jar—after initially being rejected by numerous American publishers—would become a fixture on required reading lists in high schools and colleges. For Plath, however, the recognition would come too late. On February 11, 1963, Sylvia Plath killed herself. She was 30 years old. She had two children. And her husband had recently dumped her for another woman. On the night Plath left plates of food by her children’s bedside, then sealed off the kitchen with wet towels before turning on the gas oven and inhaling its poisonous fumes, she already knew Hughes’ lover was pregnant.

It would be a mistake, though, to conclude that Plath and Hughes’ marriage (achieved within scant months of their meeting) broke down solely over his infidelity. That was more the result than the cause. In many ways, their marital troubles can be ascribed to a simple truth—as two fiercely ambitious aspiring poets, they were in love and they were in competition. But as a man, in a time when men “knew best,” Hughes was in a position to assert his authority. It was he who insisted they return to England in 1958, a year after they’d moved to America where Plath had accepted the teaching position Smith College had offered their talented alumna. Hughes had managed to get a gig lecturing at nearby UMass Amherst, but he didn’t like teaching. He told Plath he was determined to earn a living as an author and poet.

One wonders at this distance why Hughes didn’t simply do that from America? At least for a few years, to let Plath fully engage with the post she’d been given. He’d already won the prestigious Somerset Maugham Award for his collection of poetry, Hawk in the Rain, which Plath had faithfully typed up for him. He could have written from anywhere.

Plath decided she, too, would focus solely on her poetry, but the birth of their first child in 1960 vied for her time and attention. Her first collection, The Colossus and Other Poems, was published that same year. Though well-received by critics, it did not win a prestigious award. If Plath was disappointed, her response was to write more poetry, better poetry. She wrote at a feverish pace, excited about where her new verses were taking her. Then Hughes walked out just months after their second child was born in 1962. The emotional strain was intense but Plath completed the collection of poetry for what would become the crowning literary achievement of her short life, Ariel. At her death, she left detailed instructions as to how the poems should be ordered in the book. Hughes was familiar with the verses, for Plath had shared many of them with her estranged husband on those occasions when he visited the children after he moved out.

Hughes did see Ariel through to publication, spending two years on the project, but he changed Plath’s arrangement of the poems. He also omitted some poems, while adding others. These changes would earn him decades of rebuke from the new wave of feminist writers and academics who assumed Hughes had deleted Plath’s most damning verses against him. To compound the perceived offense, it was discovered that Hughes had burned Plath’s final journals.

Hughes’ “interference” in Plath’s manuscript would remain a point of contention and speculation until the publication in 2004 of The Restored Edition: Ariel, the collection of Plath’s poems as she had intended at her death. Meghan O’Rourke, writing for Slate, argued a “good case could be made that Hughes’ version of Ariel is actually superior to Plath’s,” for it included poems written in the final weeks of her life, poems she herself predicted would Make my name.

Eighteen years after Plath’s death, Hughes would edit and publish Sylvia Plath: The Collected Poems, the works Plath had published in her teens and 20s in such esteemed publications as The Atlantic Monthly, The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, and The Christian Science Monitor. To this, Hughes added some of Plath’s poetry he had omitted from Ariel almost two decades earlier. It would seem the ghost of his late first wife continued to haunt him. But the world would not realize just how fierce this haunting was for Hughes until the 1998 publication of Birthday Letters in the final months of his life. This collection of poetry from the man who was then England’s esteemed poet laureate—a man frequently cited as one of the twentieth century’s great writers—would reveal just how shattering Plath’s suicide had been for Hughes, how it had haunted him every day of his life for 35 years. Professor of English at Williams College, Lynda K. Bundtzen, noted that many of these new poems were direct responses to Plath’s own poetry. “They address her as if she’s still alive, as if he can talk to her,” Bundtzen said.

For me, the most poignant—and revealing—poem in Birthday Letters is “The Machine,” with its closing lines: …Blackly yawned me Into its otherworld interior Where I would find my home. My children. And my life Forever trying to climb the steps now stone Towards the door now red Which you, in your own likeness, would open With still time to talk.

What if Hughes had opened up his true self, his real feelings to his wife in those final months? What if he had said, “I’m sorry. What I’ve done is less than honest. Your talent feels threatening sometimes. It both amazes and scares me.” Words left unsaid are never heard. Our best intentions, our deepest feelings are never known unless we make them known. If you love someone, tell them now. Apologize for those harsh words now. Admit the mistake you made now. Express your gratitude now.

Do It Now

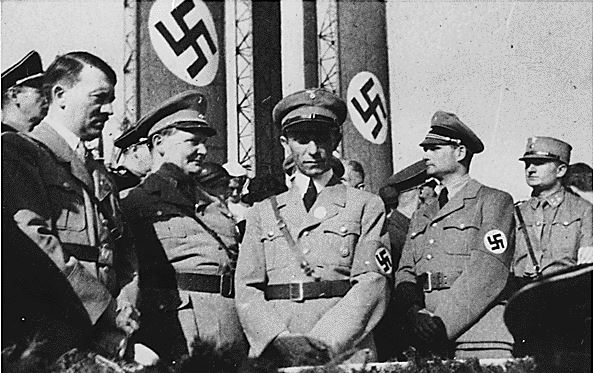

Time has a way of creeping up on us. We mean to do something, but in the hurly-burly of day-to-day life, we often put off making a decision or taking action until—poof!—the moment is gone when we can do so. Perhaps nowhere in modern history has this played out so tragically as it did in Germany when Hitler and his Nazi Party came to power in 1933.

Hitler—and this is essential in understanding people’s response—did not simply waltz into Berlin and “seize” power, as is often supposed. In fact, the Nazis (the National Socialist German Workers’ Party) had been rather small potatoes in the wake of the German Empire’s collapse after WWI. The new government, known as the Weimar Republic, considered itself a democratic institution. It held elections. It had a constitution. Under this government, Hitler spent some nine months in prison for treason when his attempted coup failed in 1924. The Weimer Republic believed the growing popularity of the German Communist Party to be a much greater threat.

But as I said, time has a way of creeping up on us. In Germany, the economic devastation caused by the post-war Treaty of Versailles, with the huge reparations it demanded for France and Great Britain, became unbearable as the world economy collapsed in the Great Depression. The Nazi Party was only too happy to lay the blame for Germany’s economic woes on the Jews and the Communists. With their message that true-blooded Germans were the real “chosen people”, the Nazis began to unite a sizeable chunk of the country. By 1932, they were winning a third of the votes in parliamentary elections—an achievement no other party could claim. German President Paul von Hindenburg at first refused to grant Hitler’s demand that he be appointed chancellor, but after various backroom deals with conservative politicians who assured him they could control the Nazi’s leader, von Hindenburg ceded to his wishes. Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933. When Hindenburg died nineteen months later, Hitler had already engineered a bill—with a little intimidation and much suspected fraud—that merged the offices of President and Chancellor into one, making him the sole leader (Führer) of Germany. The Nazis then seized control of the government and booted democracy into the gutter.

But it was a gradual coup, and the passage of time lulls people, prepares them in many ways to accept circumstances they would have once found intolerable. Acts like a narcotic— anesthetizing its victims with the thought If things get worse, then I’ll act, I’ll leave then… Because, let’s face it, leaving your homeland—your family, your house, all you’ve ever known—is the hardest thing anyone can do. And the Nazis manipulated this gradual dance with cruel brilliance.

Even before President von Hindenburg’s death, the strength of the Nazi Party in parliament had made it possible to pass laws banning Jews and other political opponents of the Reich from holding civil service positions or practicing law, with a few exemptions. But the pace of persecution kicked up a notch once Hitler took full control. The infamous Nuremberg Laws of 1935—the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor—proclaimed Judaism not a religion but a race, distinct from and inferior to the German race. Therefore, Jews could no longer vote or hold public office. As non-Germans, they had no legal rights. In 1936, Jewish doctors were banned from practicing medicine. In 1938, all Jews were required to register any property held within the Reich and Jewish students were barred from German schools.

And then Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) happened and everything exploded. This wholesale attack on all things Jewish saw synagogues, hospitals, and schools destroyed. Jewish shops and homes were burned and looted. At the end of that fiery, violent pogrom on November 9/10, ninety-one Jews had been murdered and some 30,000 Jewish men were sent to concentration camps.

Dachau, built in 1933, was the first concentration camp, a forced labor camp originally built to imprison Hitler’s political opponents—Communists, Social Democrats, and trade unionists. In the ensuing years, Jehovah’s witnesses, Gypsies, and gay men swelled the ranks, as well. Few Jews, though, were to be found at Dachau unless they belonged to one of these groups or had violated the Nuremberg Laws. Until Kristallnacht. After that, German Jews could no longer hope or believe that the Nazis were just an annoying but not mortally dangerous blip on the timeline of history—that things would surely return to normal soon, democracy would be restored. Now, every Jew in Germany understood they must leave ASAP.

Though emigration for Jews was still encouraged in 1938 by the Nazis—the fewer Jews in Germany, the better—that didn’t mean the process was smooth or, for many, even possible. To emigrate, you needed paperwork, mountains of it, much of it difficult to obtain. You needed a destination country willing to take you in. If you managed both those things, you still faced having to find some way of setting up once you arrived. Before 1938, the financial struggles of the Great Depression made many countries reluctant to take on more residents. By 1939, when emigration became easier and quotas rose in both the U.K and the U.S., the Nazis had placed a heavy emigration tax on Jews and severely restricted the amount of money they could transfer abroad from German banks. Though many would make it out, one-third of the original Jewish population would still be in Germany in 1941 when emigration was banned by the Nazis and Hitler’s “Final Solution” took effect, with its forced internment of Jews in the rapidly sprouting number of death camps. Now, it was too late.

Although genocide remains an active evil in our world—just turn on the news—most of us will not face such a dire threat, where every moment lost to hesitation, to inaction may spell the difference between life and death. But we still struggle with the human tendency to “kick the can down the road.” We put off leaving a job that bores us. We remain in a relationship that’s making us unhappy. Or we postpone getting those medical tests the doctor urged us to have.

Why do we hesitate? Perhaps a task seems difficult—too laborious (I can’t imagine undertaking all this). Or we’re not sure how to proceed (What if I make a mistake?). Maybe we’re fearful (What if the tests come back positive?). So, we put off taking the first step and thus this thing that matters—it never happens.

Revel in the Now

It would seem that no one would need to be exhorted to enjoy the moment, to revel in the now, and yet, many of us tend to come up with a lengthy list of reasons to put off pleasure when confronted with the opportunity to relax or take up some project we’ve been longing to launch into. Even something as simple as scheduling a definite date to meet up with old friends—those ones we keep messaging on Facebook: Let’s get together for drinks on our deck this summer and catch up. But June slips by, then July, then August, and “this summer” too often becomes never.

Recently I was reminded how precious—and fleeting—the “now” is. Every Sunday evening during our annual jaunt to Barbados, Ed and I go to Surfside, an open-air club on the ocean sands that features live steel pan bands on that day. For three hours, we revel in the songs of Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff, Neil Diamond, the Village People, Jimmy Buffett and a jillion other steel-pan classics. We—and when I say “we”, I mean everyone in the place—sing along with “Sweet Caroline” and do the hand motions to “Y.M.C.A.” People flock to the “dance floor”—a narrow sandy strip between the bandstand and the tables—to boogie in whatever style moves them, or no particular style at all. It is People. Feeling great. About being ALIVE.

The last Sunday of our stay, as we were munching on shrimp and drinking Rum Punch, the band struck up ABBA’s “Dancing Queen.” Ed and I looked at each other and headed for the dance floor. It’s a great song to dance to, but as I started whirling and twirling around, the lyrics played in my head: You are the dancing queen, young and sweet, only seventeen…Having the time of your life. For a moment, my heart clutched. So much time gone by never to return. How did it slip by so fast? But then I looked at Ed, at the night, the people, the stars above. Felt how much I loved it all. How much I loved this moment.

James Baldwin was spot-on. The time is always now. Say it Now. Act Now. Above all, Revel in the Now.